Environment

A Worsening Fate For The Colorado River—America’s Lifeblood

Image: Shutterstock/Doug Meek

A Worsening Fate For The Colorado River—America’s Lifeblood

It’s no secret that civilizations are built around bodies of water, which provide life and resources the same way our arteries provide blood and oxygen. But what happens when a major artery runs dry?

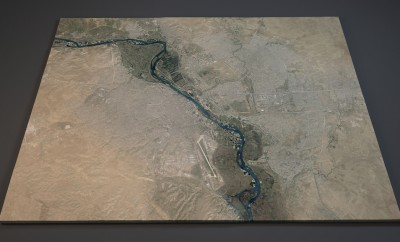

The Colorado River is the major freshwater artery of the American West and has been for at least six million years. The same body of water that carved out the Grand Canyon is now in significant danger. The river continues to flow for now, but many of its largest tributaries have already receded. The Gila River and the Salt River no longer meet in the southern reaches of Arizona as they once did, and the Colorado itself rarely makes its way to the sea ever since the 1966 construction of the Glen Canyon Dam.

The largest of the tributaries, the Green River, once combined with the force of the central Colorado to carry approximately 6 million pounds of sediment every day through Wyoming and Utah before winding all the way to Mexico’s Sea of Cortez. Today the silt is trapped by Glen Canyon and the other dams and reservoirs that drain the rivers of their force.

According to The National Geographic, the Colorado’s dire condition is due primarily to our steady increase in agricultural production, helped along by booming population growth and climate change. America’s western expansion led to taxpayer-supported farming efforts that irrigated and created canals out of the Colorado and its tributaries for the sake of growing wheat, hay, cotton, citrus and an ever-increasing roster of other important crops that together now consume roughly 70 percent of the Colorado River Basin’s water. Even beyond that whopping figure, still more of the basin’s water is used to maintain domestic comforts like suburban lawns, golf courses, swimming pools and public parks. Another 15 percent simply evaporates from our reservoirs. More than 36 million Americans rely upon the many tributaries of the Colorado River Basin, a system that encompasses 242,000 square miles of the United States, for food and water as well as for outdoor recreation.

The continued impacts of population growth and climate change will lead to progressively worse water shortages within this massive slice of North America, causing problems for the diverse array of wildlife who rely on the river even more than the West’s human population.

The emptying of the Colorado River Basin hasn’t gone unnoticed, and there are many restoration efforts already underway. One effort aims to help the ancient species of fish such as the pike minor and the razorback sucker that have become endangered due to dams and reservoirs that block their migration paths. These species have declined while other non-native sport fish thrived, serving the greater need of a similarly increased human population. The population of the states within the basin has increased ninefold since the Colorado’s waters were apportioned to the seven separate states, and the demand for water has increased with it.

NatGeo’s Jonathan Waterman has taken it upon himself to document the effects of our increased development of the Colorado River, taking photos of specific locations to compare with long-ago archived photos of the same area to show the changes that have occurred within the past century or so—hardly anytime at all, given the Colorado’s six million year lifespan.

Yet the river’s evolution in this short stretch of time is nonetheless harrowing. “Sometimes,” Waterman writes, “the scenes are so overgrown with towering invasive plants that I can’t see, let alone photograph, the river.” When his hard work does yield results, as it often does, Waterman’s photographs make for tragic supplemental materials to early photographs of the untamed American West captured by the likes of Louis C. McClure, William Henry Jackson and Timothy O’Sullivan. The West has been tamed, and the comparative photographs reveal a world where dry brush and irrigated planned communities have replaced the natural bodies of water that first gave those communities life.

Trying to anticipate the continued effects of climate change and human expansion would be an uncertain prediction at best, but recent studies suggest the Colorado River’s flow may decrease by 8.7% or more by the year 2060. The figure might seem small by other standards, but such a decline would deprive the entire Los Angeles metropolitan area of half its water supply.

The Colorado River is an essential part of the American economy, providing space for recreation, construction, agriculture, tourism and the associated employment afforded by such industries. There are plenty of efforts to revive the declining artery of the American West, but without a significant change in the current trend, it isn’t hard to imagine the region deprived of its historic lifeblood.

0 comments