Cultures

The shocking number of suicides in the Attawapiskat community

Since September, the First Nations aboriginal community of Attawapiskat of about 2,000 people in northern Ontario, Canada, has had 101 of their residents attempt suicide. Thirteen-year-old resident Sheridan Hookimaw sadly completed hers, to the shock of many, by hanging herself in October. After eleven more residents attempted suicide in a single recent day, the chief and community council declared a state of emergency. This was not the first of such declared states, nor waves of attempts, for this or other such aboriginal communities. Families are again hiding medication, ropes and knives. The possible reasons are multifold and plentiful. Lack of access to clean tap water, geographical isolation, lengthy, severe winters, substandard housing conditions and a lack of resources touch on some of the community’s issues, but an understanding of history is also needed.

The situation is dire

As with many aboriginal communities, Attawapiskat is a place of poverty. Since Indian Act requirements of the late nineteenth century forced traditionally nomadic hunting and fishing communities onto remote reservations, most of the residents are currently living in homes and on land they do not own, or, more correctly, no longer own. Water is dangerously contaminated with methane in levels far higher than any health standards permit. Bottled water is only provided at distribution points and residents are advised to limit showers to five minutes or less to avoid prolonged exposure. The only way into or out of town for travel or provision of goods and supplies is by air or via an ice road that is only open from January to early March. Houses are frequently condemned due to sanitation backups or poor insulation (unacceptable when the weather often reaches temperatures below negative 35 degrees), with the result being families needing to live together in large numbers, it is not unheard of, for example, for as many as twenty family members to live together in a two-bedroom home. Nearly half the school-age children drop out of school before graduation and oxycontin, called “the poor people’s heroin,” is a very common habit, along with alcohol abuse, among adults. And although the community is within close proximity to the De Beers open-pit diamond mine, available jobs are sparse and unemployment rates remain high. Many hunt caribou and moose, fish, or have a few jobs in the town to support themselves, while others are fortunate enough to work at the De Beers mine or otherwise receive government benefits.

The hospital is very short-staffed

Astoundingly, the community’s small 15-bed hospital has no regular doctors—only those who are willing to fly into town four days out of three weeks monthly. The overnights and weekends are left to only two nurses. According to the hospital’s patient care coordinator Melanie Phelps, when the largest number of suicide attempts took place, mostly children ages 9-14 who were suspected of ingesting pills, patients had to be medavaced to a nearby hospital for treatment. It should be noted that community members of all ages have attempted suicide, in fact, not just children, which makes the situation even more complex.

There is hope

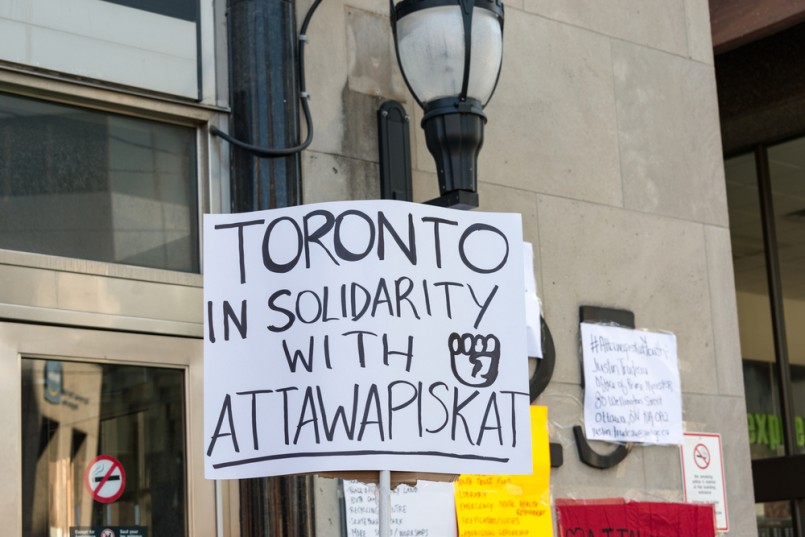

Just as remarkable as the poverty and struggles, however, is a remarkable closeness, resilience and love among Attawapiskat resident families. Young people hold healing marches together through many First Nations communities to build awareness of the issues, Health Canada has sent in mental health counselors, millions in short-term aid and emergency assistance teams to assist in 24-hour health care, and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has promised to “rebuild the relationship with aboriginal groups.” All are helpful measures, indeed, but for Stephanie Hookimaw, mother of 13-year-old Sheridan, and the only completed community suicide, the state of emergency came about just a bit too late. Perhaps the secret lies in maintaining the strengthened relationship, once achieved, and providing continued relief services and assistance along with alleviating the poverty and substandard housing. Perhaps these are the minimum owed to Sheridan’s and other families who’ve endured such unspeakable loss.

0 comments