Cultures

Why the French are fascinated with America’s Wild West

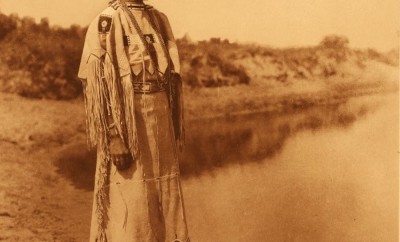

Image: Rarefilm

What happens when a French Western features Jean-Pierre Léaud, the darling of the New Wave, acting like a complete stooge? You get Luc Moullet’s ‘A Girl is A Gun’ – a wild tale of two bandits stumbling through the Southwest desert to reach refuge in Mexico. All we know is that Léaud, playing the character of Billy the Kid, stole several purses of golden coins and has the authorities hot on his chase. He stumbles into Kate, a wily trickster femme played by Rachel Kesterber, and fearfully decides to kidnap her. Their chase together is perilous, exhausting, sinister, and deeply foolish.

Billy runs into a tree. Billy falls into a hole. Billy is a goon. In an epically dramatic moment, Billy cries out that he wants to be left alone to die in the desert. Kate begins to tease him, slowly undressing herself and scurrying away. Billy’s sudden virility gives him a spurt of life, as he prances and dances and chases after his prize. Their ultimate embrace is visually represented through images of crawling cockroaches, and the surreality of intimacy in the scorched desert comes full circle. This, friends, is Goon-Wave.

(Spoiler Alert) As Billy and Kate finally reach the promised land of Mexico and find water, Kate reveals her underlying motives throughout their journey. She had been the wife of someone Billy had killed in a hold-up and plotted her revenge against him. She gave herself to him, hid his knife, sabotaged his plans, and intentionally redirected them away from water, all in pursuit of wooing him into falling in love. Then, she would kill herself, and thus take away the object of his love, as he had previously done to her.

But she stops short. After the reveal, Kate releases him to his anguish and then narrative completely disintegrates. In a delirious stumble, he bumps into an indigenous girl, and in the next scene they are married. Then Billy pursued extensively by another indigenous man until he finally escapes and somehow finds himself reunited in Kate’s arms.

Moullet’s French New Wave Western came out a year after Jodorowski’s legendary El Topo and the recent successes of Italian Neorealist Westerns. The film skates between satire of both the Western and New Wave genres, leaving characters dramatically undeveloped and unintentionalized. The French New Wave’s desperate and roaming aesthetic finds its perfect match in the desolate and lonely landscapes of the American West. The archetype of an incorrigible devious male protagonist finds its satirical simulation in Léaud’s memorable performance. Billy has lost the charm of Godard or Truffaut’s wandering anti-heroes. Here, Léaud is pitiful, desperate, embarrassing, and doomed.

The final disintegration of the film announces the death of the genre. If the French Wave’s aesthetic was holding together by a thread, it has now been shot into a thousand pieces. The story collapses into itself, showings strands and threads and a thousand directions, as aimless as life itself.

0 comments