Environment

Yvon Chouinard: Environment First, Business Second

Image: Why Choose Only One

Yvon Chouinard: Environment First, Business Second

Simplify your life. It’s a lot more satisfying.

When people think of the brand Patagonia, they either see photos of climbers, fly fishers, and outdoorsmen sporting high-quality gear, or they see Southern college students dressed in pullovers and fabricated fraternity and sorority T-shirts with the classic striped logo. The latter of the two is what gave the brand the stereotype, Fratagonia. To no one’s surprise, I utterly despise this nickname as it’s nowhere near representing the brand that Yvon Chouinard founded at camp 4 in Yosemite. And in typical Yvon Chouinard fashion, I have no reservations speaking my mind about what I think needs to be changed. In this case, the reputation of Patagonia and the amount of information people know about its founder and owner, Yvon Chouinard, needs to be changed.

Chouinard is a promoter of exploring the earth through physical activity and spending as much time as possible in the outdoors, but he is an even bigger promoter of spending less, buying less, and especially polluting less. This is why Patagonia creates and sells things you need and things that are of such high quality you shouldn’t need to replace them. If your product does fail, Patagonia’s Worn Wear system will fix the product up for you instead, or they’ll teach you how to do it yourself. If you no longer want your Patagonia clothes, the brand will help you sell your item on eBay or in-store at a good rate. Chouinard even says, “Think twice before buying something from us.” One full-page ad in The New York Times even stated, “Don’t Buy This Jacket.”

People don’t need fancy stuff–they need gear that lasts and that works well. I’ve built my company based on that.

Image: Wiki Commons

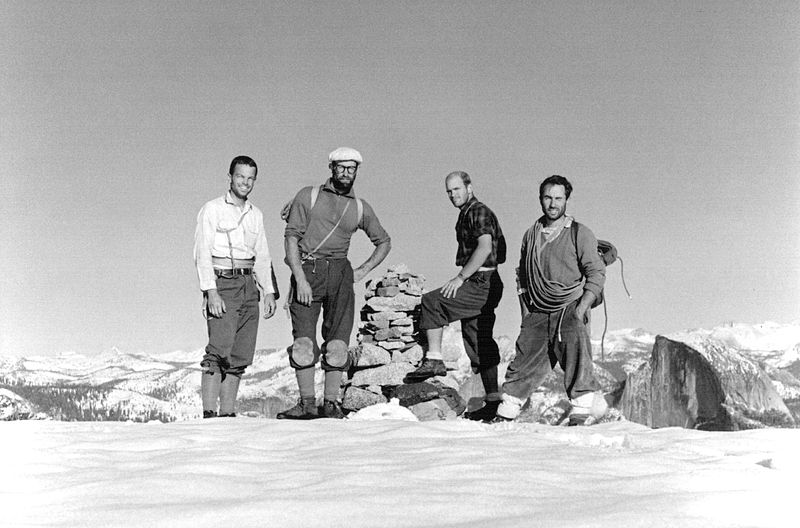

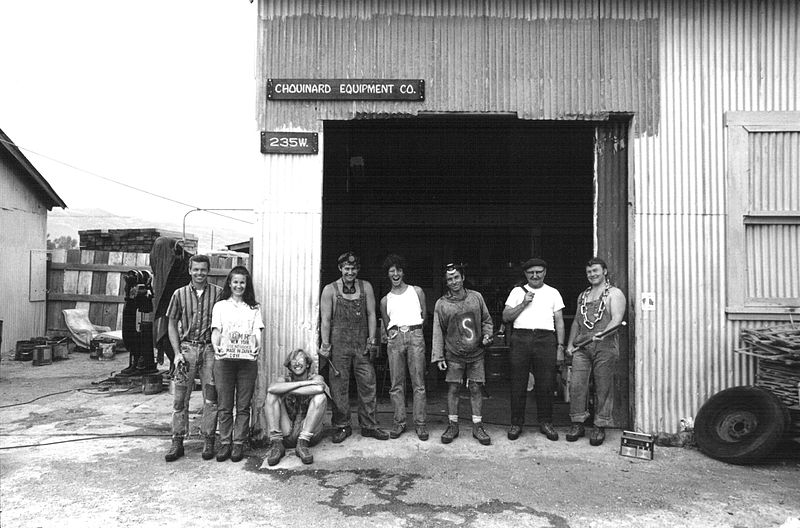

Chouinard, who began climbing at age fourteen and who settled into Yosemite’s famous camp 4 with climbing stars like Royal Robbins, is not your typical outdoorsy guy that decided to build an outdoor clothing brand. In fact, Patagonia began as Chouinard Equipment Co. after Chouinard realized he needed pitons to climb multi-day ascents at Yosemite. In 1957, he bought used, coal-fired forge, a 138-pound anvil, tongs and hammers at a junkyard, and he taught himself how to blacksmith. From the beginning Chouinard was a resourceful, hard-working entrepreneur that aimed to leave as little of a footprint as possible.

The handmade pitons were first used on early ascents of the Lost Arrow Chimney and the North Face of Sentinel Rock in Yosemite. Aspiring climbers flocked to Chouinard requesting his chrome-molybdenum steel pitons. He sold them for $1.5o, and just like that Chouinard had started his own business.

Image: Wiki Commons

Chouinard Equipment had become the largest supplier of climbing gear in the U.S. by 1970, but there was a catch. These pitons had a severe environmental impact. Chouinard and his business partner Tom Frost climbed the nose of El Capitan and noticed the degradation on the rock that had not been there just a few summers before. The two decided to phase out of the piton business even though it was their biggest source of income and the most-wanted gear in climbing. This was the first large-scale environmentally-conscious decision that they would make.

Luckily, Chouinard and Frost found an alternative—aluminum chocks that could be wedged by hand instead of using a hammer. These were introduced by Chouinard Equiment in their 1972 catalog, which opened with editorial content about the environmental hazards of pitons. This was much like today’s Patagonia catalogs, which read more like environmental non-fiction than a shopping catalog. The 14-page essay was written by Sierra climber Doug Robinson, who explained that “clean climbing” is using only nuts and runners.

Clean because the rock is left unaltered by the passing climber. Clean because nothing is hammered into the rock and then hammered back out, leaving the rock scarred and the next climber’s experience less natural.

This was the start to the environmentally-minded company that is so well-known today—though perhaps not for its impactful environmental initiatives.

Patagonia’s first step toward grassroots action for the environment began when a group attended a city council meeting to protect a local surf break. The Ventura River, which had once been a major steelhead salmon habitat, was being harmed by two dams that were built in the forties. At the meeting experts testified that the river was dead and that the dams had no effect on remaining wildlife on the surf break. Mark Capelli, a 25-year-old biology student, presented a slideshow of wildlife, including steelhead, that still came to spawn in the “dead” river. Mark was given office space at Patagonia and small contributions to help his fight for the river. Eventually the river was cleaned up, the water flow increased, and the steelhead began to spawn.

This case brought up two major lessons for the company. The first was that grassroots effort can really make a difference, and the second lesson was that degraded habitat could be restored with proper work and restoration. Since 1986, Patagonia has chosen an enormous amount of small environmental groups to donate 1% of their sales to (or 10% of profits when it’s a greater number).

Image: Wiki Commons

Patagonia’s first national environmental campaign in 1988 was an initiative to deurbanize the Yosemite Valley. Each year the company undertakes a major education campaign on some environmental issues. These have included attacking globalization of trade when it compromises environmental and labor standards, pushing for dam removal, and supporting wildlands projects.

In addition to leading their own environmental campaigns on a regular basis, Patagonia holds a “Tools for Activists” conference every eighteen months to teach marketing and publicity skills to environmental small groups and leaders.

With all the work Patagonia does outside the company, it is equally important to note the efforts they’ve taken to make their own business tread lighter. Patagonia catalogs have been using recycled-content paper since the mid-eighties, and they use recycled polyester for the Synchilla fleece. The distribution center uses solar-tracking skylights, radiant heating, and recycled content for the building and its features. Colors that require the use of toxic metals and sulfides have been removed from all product lines.

One team discovered that 25% of all toxic pesticides used in agriculture is used in the cultivation of cotton, and that the resulting pollution of soil and water is horrific. There is also strong evidence of damage to the health of fieldworkers. Farmers used to grow cotton organically (without pesticides) for thousands of years before machines added chemicals to the process. By 1996, Patagonia’s cotton products were 100% organic.

Patagonia is consistently an open book when it comes to how their products are made and what the brand and its people represent.

We can’t bring ourselves to knowingly make a mediocre product. And we cannot avert our eyes from the harm done, by all of us, to our one and only home.

In an interview with The Usual, Chouinard explains that ultimately we’re the problem, not big corporations or governments.

We’re the ones telling the corporations to make more stuff, and make it as cheap and as disposable as possible. We’re not citizens anymore. We’re consumers. That’s what we’re called.

So, there’s a movement for simplifying your life: purchase less stuff, own a few things that are very high quality that last a long time, and that are multifunctional.

0 comments