Cultures

A film’s spiritual journey through the majestic Colombian countryside

Image: imdb

As a visual medium, film seeks to represent material reality—the body and bread. But what of the becoming? What can the cinema do for our interiority, our subjective experience of thought, feeling and spirit? How does film capture the soul?

In Ciro Guerra’s statement concerning his 2009 drama The Wind Journeys, the Colombian filmmaker articulates his spiritual intention:

“This is the story of a journey, a journey towards the beginning, towards the spirit…towards our soul.”

Here, I would like to reflect on how Guerra experiments with stylistic elements in The Wind Journeys to communicate ontology and visually reach toward the invisible.

The Wind Journeys follows vallenato folk musician Ignacio Carrillo on his voyage to return his cursed accordion to its original owner, his former teacher. As he takes off, Ignacio is met by Fermín, an eager teenage boy who is determined to become the old troubadour’s apprentice. The two set off on a wild and penniless adventure, involving accordion duels, machete duels, chicken fights, initiation rites and the epic panoramic vistas of northern Colombia.

While Guerra’s The Wind Journeys is narratively structured around Ignacio’s objective to reach the mountain peak where his former teacher resides, it quickly becomes clear that their expedition is secondary to each character’s emotional processes. Ignacio mourns the loss of his recently deceased wife, croons more than he speaks, yet ultimately remains ambivalent about his craft, having sworn to never play again. When an indigenous doctor heals his machete wounds, we’re told,

“He’s alive, but he doesn’t want to live anymore. He’s tired of living.”

Ignacio’s rugged malaise is contrasted by Fermín’s impulsive yearning for acceptance and mentorship. Fermín throws himself into risky situations to seek approval, like interrupting an initiation rite for a cultic drummer’s circle to receive a lizard blood baptism. When the two finally reach the plateau where Ignacio’s mentor supposedly lives, Fermín admits,

“I didn’t come to find him.”

Fermin, rather, has drifted along aimlessly, as if blown by the wind itself.

To capture interiority, Guerra frequently uses long stills with a wide-angle lens in The Wind Journeys, situating his characters within their immediate context. Whereas a close-up is an obvious and overbearing gesture to what lies beyond or within, the wide-angle portrait creatively constructs a dialectic between the emotionality of majestic landscape and Ignacio and Fermín’s shared solitude.

Image: ytimg

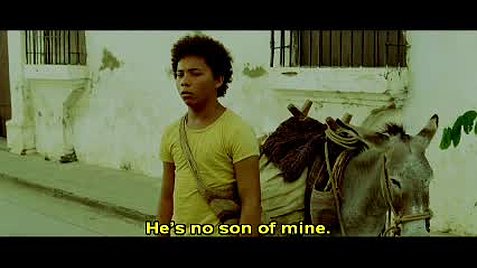

Secondly, Guerra composes a rhythmic tapestry of short dialogues and long silences to prompt ontological inquiry without resolve or conclusion. When a threatening villager insults Fermín, Ignacio harshly responds,

“He’s no son of mine.”

The viewer is left with a long take of Fermín, despondent, pensive, ever determined.

Image: imdb

Finally, Guerra conveys the travelers’ emotional landscape through gorgeous depictions of the Colombian natural landscape in The Wind Journeys. Ignacio and Fermín are caught between wondrous valleys, misty plateaus and golden farmlands, as they ever slowly move toward the distant mountain. Their journey is consistently derailed by violent brutal masculinity. Man is the countryside’s counterpoint. But as the travelers narrowly escape each trial, they find their peace in silence in the outdoor journey itself. The sensuousness of the majestic images suggests that Ignacio and Fermín are ultimately roaming an internal vastness.

The Wind Journeys is an odyssey taking Ignacio and Fermín far away from home in order to rediscover their sources. The travelers must reach the end of the Earth to find their purpose, that is, their beginning.

0 comments